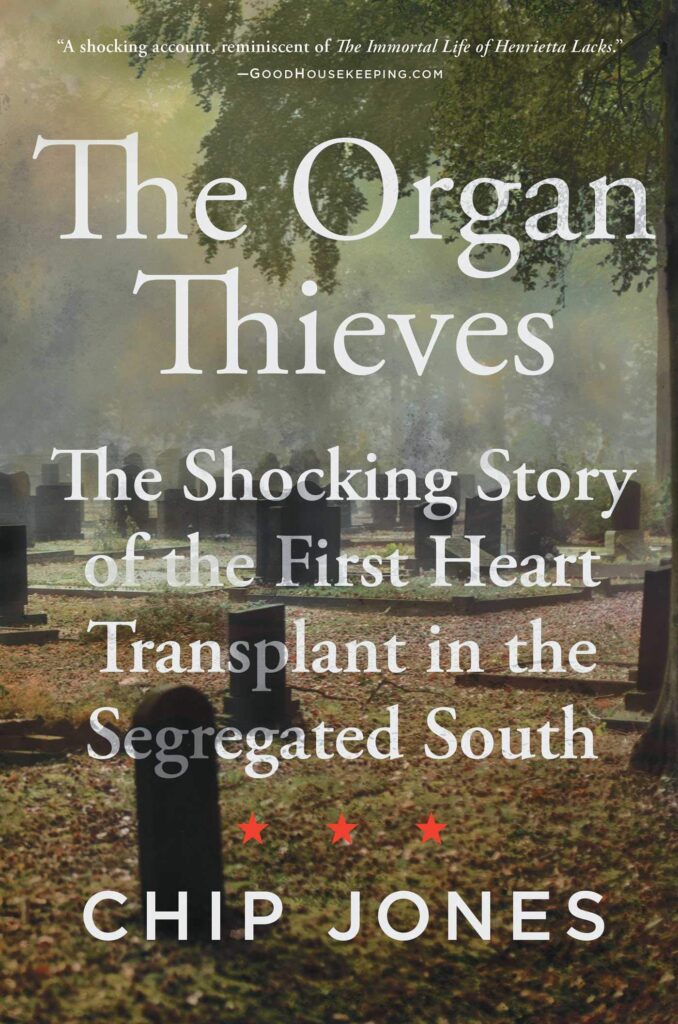

This true account of the history of organ transplantation in the South is as shocking as it is detailed. Journalist Chip Jones’ thorough research is expertly woven among a scintillating narrative, sparking the readers’ interest from the very first page. While the nation struggles to properly address the Black Lives Matter movement, this book could not be more timely in its inward look at systemic racism in our medical and legal institutions, and how our technological advancements have been tempered by the vast amounts of inequality at every turn.

The Organ Thieves: The Shocking Story of the First Heart Transplant in the Segregated South, while shocking in content, only confirms more of what many people of color in this country have known for centuries: Black people have had the odds stacked against them since they disembarked from slave ships in Jamestown. Two hundred years after the first slave ship arrived from the Middle Passage, Black lives were still subject to atrocities of all kinds. In this specific case, medical experiments in the pursuit of advancing modern medical techniques and processes. The Organ Thieves proves that we have built some of the cornerstones of society on the backs of black bodies.

Delving into the history of medicine in America during a global pandemic is no easy feat, and Jones breaks down the evolution of medical training in the 1950’s in an approachable, pointed manner that uses thoroughly researched anecdotes to draw in the reader. His story takes place in his native Richmond, Virginia, and centers around the dubious, yet critically acclaimed practices that took place at the Medical College of Virginia (MCV).

The history of organ transplantation is complicated, cut throat, and fundamentally driven by ego, not to mention a lawless space reminiscent of the wild west. Federal legislature has had a difficult time keeping up with both medical and technological advancements over the past fifty years, ultimately being forced to play catch up as a result of trial and error medical procedures. Cadaver hearts, cooling recently extracted organs in an icy saline solution, and utilizing the organs of animals like baboons and dogs have all played a role in establishing protocol and best practices for organ transplants. This has been especially important for the two organs that most often require a transplant: the heart and the kidneys.

Though the lead surgeons and main characters of this story at MCV desperately wanted to be first in the global race to successfully complete a heart transplant, Drs. Humes and Lower mitigated substantial risk in waiting to attempt a surgery that is, decades later, still incredibly risky. The crux of this story lies in whether or not their protocol was accurate when they were finally ready to perform the procedure.

Jones calls into question the then-unregulated practice of organ donation, a piece of the twenty-first century medical puzzle that is still troubling to this day in the U.S. In other first world countries, unless your driver’s license specifically indicates otherwise, you are considered an organ donor. Like universal healthcare and voting from your computer, this is a practice that never fully caught up with the social progression of this nation the way it did in others.

The most thought-provoking part of this story actually occurs two years after the MCV surgical team completes the hospital’s first successful organ transplant, when they are sued by the family of the organ donor, Bruce Tucker, who was admitted to MCV after falling off a wall and suffering from a brain injury.

Did this elaborate, learned team of doctors really do everything possible to locate the organ donor’s next of kin? Was Tucker’s racial and socioeconomic status and his seeming lack of a family part of the decision making process in pronouncing him dead at noon and removing his organs mere hours later? And moreover, at what point is it legally acceptable to pronounce someone dead?

The book culminates in the aftermath of this trial, and boils down to a spooky concept: what is the definition of death, and what is the difference in the eyes of the law versus the eyes of medicine.